Already 45 years in space

Voyager’s sensors have gone too far

2/7/2022 4:54 PM

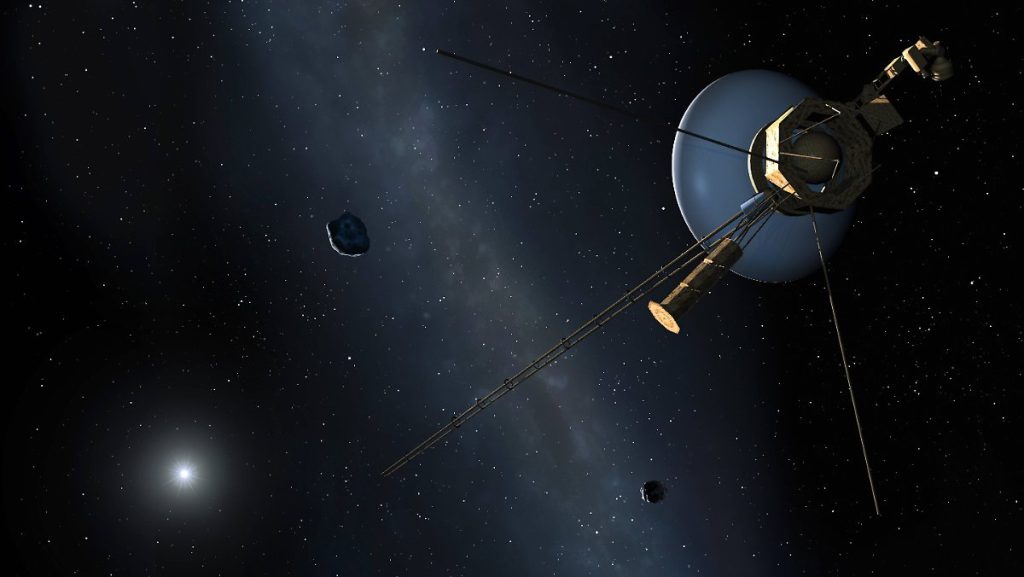

The Voyager space probes have been moving for about 45 years. Today it is the furthest man-made object from Earth and has penetrated previously unexplored areas for a long time. But now they are starting to weaken.

Far, Far, ‘Voyager’: Man-made objects have never moved as far from Earth as these two Dual sensors from NASA. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have been on the road for about 45 years. Since then, both have left the heliosphere and entered regions that had not been explored by spacecraft before.

But the longest flight in space history appears to be drawing to a close: Although both unmanned probes are still flying and continue to send data, the NASA scientists responsible have already grounded several onboard instruments in the past three years in order to extend The remaining. energy. The power of the sensors is decreasing year by year – and engineers have to adapt to it. To do this, they often have to read decades-old documents or contact long-retired NASA engineers.

With Voyager 1, scientists are currently having a data problem. Although the probe is operating normally, the control system displays completely different data. “Such a puzzle is not surprising at this point in the mission,” said lead scientist Susan Dodd. “The two probes are about 45 years old, much longer than mission planners ever expected. We are outside the heliosphere — a highly radioactive environment in which no spacecraft has ever flown. So for engineers, there are major challenges.”

Originally, the “Voyager” (German: traveller) mission was designed by two “cosmic astronauts,” considered one of the most successful projects in NASA’s history, for four years. “Voyager 2” was launched on August 20, 1977, and its twin sister “Voyager 1” shortly thereafter on September 5, 1977.

Beyond all limits

Both probes, each weighing about one ton, had a rendezvous with Jupiter and Saturn, “Voyager 2” visited Uranus and Neptune. The probes also studied nearly 50 satellites. The pair have sent back stunning images of Jupiter’s atmosphere, active volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io, and Saturn’s rings.

As an insight, the sensors were equipped with backup systems from the start. Duo Voyagers are powered by long-lived plutonium generators.

Voyager 1 is now more than 23 billion km from Earth, farther than any other spacecraft, while Voyager 2 is about 20 billion km away. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft in human history to leave the solar system. Thanks to its previous launch, Voyager 2 is the longest continuously operating spacecraft. In 2018, Voyager 2 also left the heliosphere.

However, there are different definitions of the limits of the solar system. It is often equated to the edge of the heliosphere, a type of bubble in interstellar space that is formed largely by the solar wind. According to other experts, the boundary is farther and lies behind the so-called Oort Cloud, a group of small objects that, despite the huge distance, are still under the influence of the Sun’s gravity.

Music in the bag

“Our energy budgets are getting tighter, but our team assumes we can do science for at least five more years,” the probes recently said via Twitter. “Maybe we will be able to celebrate our 50th anniversary or even work in the 2030s.”

Even if they were silent, the sensors would not stop flying. They are currently traveling through the Milky Way at about 61,000 kilometers per hour (“Voyager 1”) and about 55,000 kilometers per hour (“Voyager 2”). The “Voyager” twins have them on the music data carriers of rock and roll legend Chuck Berry, as well as the classical music of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, as well as sounds from countries like Australia, Bulgaria, Japan and Peru and 115 images and greetings of potential aliens in 55 different languages.

“It’s hard to see the end coming,” scientist Alan Cummings, who has been tracking the probes for decades, told Scientific American. “But we did great things.”

“Total coffee aficionado. Travel buff. Music ninja. Bacon nerd. Beeraholic.”

More Stories

Coral Seeding: Artificial Insemination Makes Coral More Heat Tolerant

Fear, Anger, and Denial: How People Respond to Climate Change – Research

LKH Graz: Using radiation to combat heart arrhythmias