Mysterious pause: a white dwarf about 1,400 light-years away baffles astronomers. As the remnants of stars show a sudden sharp drop in brightness – the luminosity drops dramatically in just 30 minutes. Such a rapid change had not previously been observed in a white dwarf, the researchers reported in the journal Nature Astronomy. So far, she can only speculate about the cause of these light pauses.

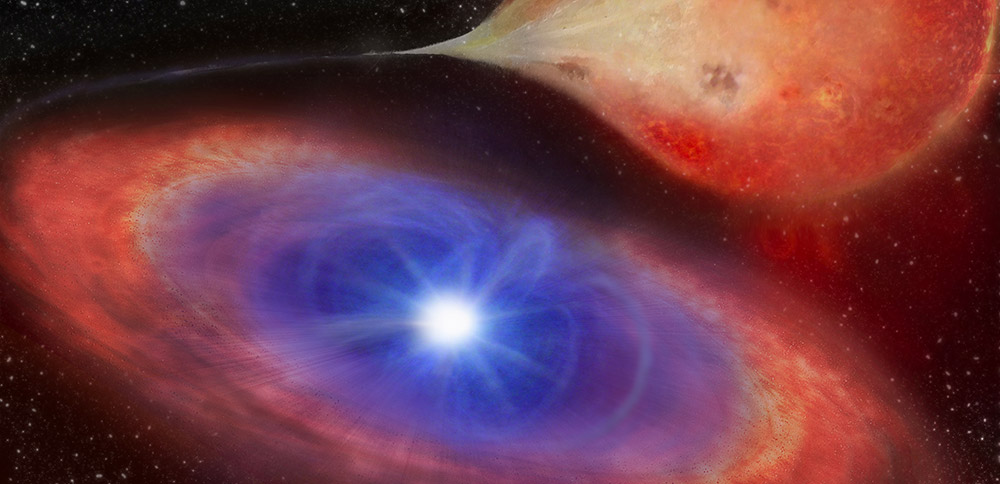

If the stars are like the sun end of their life cycle Arriving, they end up as white dwarfs – scorched remnants of stars that gradually cool and become darker. However, if a white dwarf is part of a binary star system, it can achieve new vitality at the expense of its partner: it absorbs material from the partner star, thereby reheating its nuclear fusion. This can continue until the white dwarf resembles “overeating” by exceeding the critical mass and Supernova type 1a Explodes.

strange fluctuations

At first glance, the white dwarf in the twin star system TW Pictoris, 1,400 light-years away, is also nothing special: it constantly sucks material in the form of hydrogen and helium from its smaller companion star, thus shining very brightly to the rest of the star. However, contradictory measurements of its luminosity provide for a long time to guess: sometimes it seems that the brightness of a white dwarf decreases by as much as three times.

To get to the bottom of this phenomenon, Simon Scaringi of Durham University in England and his colleagues repeatedly examined the white dwarf from TW Pictoris using NASA’s TESS Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. This telescope specializes in detecting even the smallest changes in a star’s light curve, such as those caused by an exoplanet passing in front of its star.

suddenly shuts down

But when astronomers evaluated the TESS light curves from TW Pictoris, they discovered something surprising: “Amazingly, the TESS observations reveal sudden, sudden changes in the system’s luminosity, in which the brightness by a factor of 3.5 in less than 30 minutes is decreasing,” according to a report. Scaringi and his team. The white dwarf became noticeably darker in a very short time – as if it had shut itself down.

“Usually, the brightness of an incoming white dwarf changes relatively slowly — over the course of several days or months,” Scaringi explains. “It is unusual that the brightness of TW Pictoris decreases in only 30 minutes. This has not been observed before in a white dwarf and is completely unexpected from our understanding of such systems. It appears to turn on and shut down itself.”

In most cases, it took between a day and two months after this “lockdown” before the white dwarf regained its normal luster. Astronomers also noted several times that the sudden drop in brightness lasted for a very short time and that the remnants of stars recovered almost instantly.

Magnetic barrier blocking the road

Also strange: even during the sudden outage and the subsequent phase of low brightness, the flow of matter from the partner star to the white dwarf did not stop. However, it was noted that during this “dark” phase there were more short radiation bursts that repeated every 1.2 to 2.4 hours. “Such quasi-periodic outbreaks in the optical range are typical of low mass transfer rates,” the researchers explained.

From this the astronomers concluded that although the flow of matter into the white dwarf does not stop, it can suddenly absorb less matter. The magnetic field of the rest of the stars may be one possible reason for this: When the white dwarf is “off,” the rapidly rotating field may form a kind of magnetic barrier that prevents gas from reaching its surface. Although there is a sufficient supply of the material, the white dwarf can only absorb it to a small extent and its brightness decreases as a result.

What is the cause and what is the effect?

In other words: the white dwarf “dies” in front of a full plate. Only now and then a sting of material penetrates the magnetic barrier and causes short bursts of radiation. Only when the star’s remnant changes back to its “operating state” does the magnetic barrier fall and can pull unimpeded from its neighbor’s star’s material. “This behavior establishes a previously unknown phenomenon in growing white dwarfs,” the astronomers say.

The reason for these rapid changes is still unclear and what effect they will have. On the other hand, the magnetic barrier can arise only through a temporary decrease in the rate of accumulation, as explained by Scaringi and colleagues. Conversely, however, an abrupt reconfiguration of the magnetic field – eg through a change between two unstable states – can turn it on and off.

Similarities with millisecond pulsars?

Also interesting: in some aspects, the behavior of the white dwarf from TW Pictoris is similar to that of some Transient pulsars milliseconds Neutron stars that suddenly switch between a powerful X-ray source and a radio pulsar. With them, too, he participates in the accumulation of matter from a companion star. According to astronomers, these parallels could indicate that there is a similar mechanism behind both phenomena.

“This discovery could be an important step toward understanding the processes by which other bodies also absorb the matter they absorb, as well as the role that magnetic fields play in this process,” Scaringi says. Now astronomers hope to be able to track down other white dwarfs that exhibit similar sudden shutdowns. This can help unravel the mystery of TW Pictoris and other joined orbs. (Natural Astronomy, 2021; doi: 10.1038/s41550-021-01494-x)

Coyle: Durham University

“Total coffee aficionado. Travel buff. Music ninja. Bacon nerd. Beeraholic.”

More Stories

Coral Seeding: Artificial Insemination Makes Coral More Heat Tolerant

Fear, Anger, and Denial: How People Respond to Climate Change – Research

LKH Graz: Using radiation to combat heart arrhythmias