October 17, 2023 Reading time: 4 minutes.

Atoms beyond what is known: Some asteroids have inexplicably high densities, and no previously known element is heavy enough to do so. But there may be more elements in space than the 118 recorded in our periodic table, as physicists now assume. According to their calculations, elements containing about 164 protons could be stable and heavy enough to explain the presence of ultra-dense asteroids. However, detecting these large atoms may be difficult or impossible.

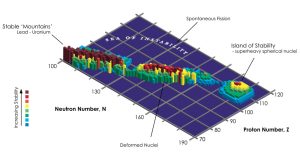

How vast is the range of elements in the universe? How complete is our chemical periodic table? With the discovery of superheavy elements with atomic numbers 113 to 118, the seventh and lowest period of the atomic table was completed – for the time being. But it is uncertain whether there are other atoms heavier than the known elements. The fact that all previously known superheavy elements are extremely unstable and disintegrate after only a fraction of a second, contradicts the existence of other elements. The large number of protons increases their mutual repulsion.

© Inviderxan/ CC-BY-SA 3.0

On the other hand, nuclear physicists have long suspected that there might be an island of stability beyond currently known types of atoms—a region where certain interactions between nucleons stabilize the atomic nucleus despite repulsion. One of these hypothetical islands of stability could be in atoms with 126 protons and 228 neutrons, and another with 164 protons and 308 or 318 neutrons.

The secret of super dense asteroids

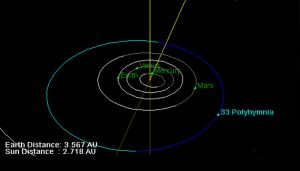

Here comes the role of the study conducted by Ivan LaForge and his colleagues from the University of Arizona. Their idea: It is possible that hitherto unknown superheavy elements could explain why some asteroids in the solar system are heavier and denser than is actually possible. “The asteroid (33) Polyhymnia is particularly notable: based on mass and volume measurements, its density was calculated to be 75.3 grams per cubic centimeter,” the researchers said.

The strange thing is that the densest stable element in the periodic table is the heavy metal osmium, with a density of 22.59 grams per cubic centimeter. But the density of the asteroid Polyhymnia is more than three times greater – and this cannot be explained by previously known elements. “The mass density of this asteroid is much higher than the maximum density of known atomic matter,” LaForge and his colleagues explain. “So we wanted to explore whether these compact ultra-dense objects (CUDOs) could be composed of superheavy elements outside the periodic table.”

Calculated radii of superheavy elements

To find out the density of elements above atomic number 118, LaForge and his team used the so-called Thomas Fermi model. This refers to how large the radius of a metal’s positively charged atomic nucleus is – the part of the atom that includes the nucleus and the electrons that are still tightly bound to it. In heavy metals and metals, some of the outermost electrons form a delocalized “electron lake” – making the metals good conductors of electricity and heat.

The density of metal atoms depends primarily on the radii of their atomic bodies. “We used the Thomas Fermi model because, despite its relative imprecision, it allows a systematic exploration of atomic behavior as a function of the number of protons – even outside the known periodic table,” explains senior author Jan Ravelski. After he and his team applied the model to verify known minerals, they also used it to calculate elements up to atomic number 164.

Element density 164 fits polyhymenia

Result: According to calculations, element 164 should have an atomic radius between 0.13 and 0.16 nanometers. “From this we conclude that the density of element 164 must be between 36 and 68.4 grams per cubic centimeter,” physicists say. If this element exists and is stable, as is assumed for the elements on this “island of stability,” this may explain why the asteroid (33) Polyhymnia is inexplicably so heavy.

“If a significant portion of the asteroid was composed of such superheavy metals, its mass density would be close to the observed value,” explain LaForge and his colleagues. This proves that such compact and ultra-dense objects can also exist without dark matter or exotic forms of matter.

Do “superheavy objects” even exist?

However, whether these superheavy elements exist outside our periodic table is still unclear, and will likely remain so for a while. Producing these large atoms in the laboratory is extremely difficult or even impossible. “All superheavy elements — both unstable elements and those yet to be discovered — are usually grouped together under the name ‘unobtainium.’ In German this means something like ‘unreachable,’” says Radelski.

“The idea that some of these elements are still stable enough to occur in our solar system is even more exciting.” (The European Physical Journal Plus, 2023; doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-04454-8)

Source: European Physical Journal Plus, SciencePOD

October 17, 2023 – Nadia Podbrigar

“Total coffee aficionado. Travel buff. Music ninja. Bacon nerd. Beeraholic.”

More Stories

Coral Seeding: Artificial Insemination Makes Coral More Heat Tolerant

Fear, Anger, and Denial: How People Respond to Climate Change – Research

LKH Graz: Using radiation to combat heart arrhythmias