In principle, these pulsars not only send radio radiation into space, but also cover the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Now catching gravitational waves with gamma rays

High-energy gamma rays have an unbeatable advantage over radio waves: they are not affected by the interstellar medium. In this respect, gamma radiation provides an advantage over high-resolution measurements in the radio band, as this source of error does not exist there. On the other hand, gamma rays cannot be directly observed on Earth, as they are absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere – fortunately for us, one must say.

© Daniëlle Futselaar / MPIfR (Artsource.nl) (Details)

The Fermi Large Telescope (LAT) on the Fermi satellite | The researchers can also look for the background of low-frequency gravitational waves in the gamma-ray band. How convenient is it to have a gamma ray space telescope in Earth orbit for several years.

Fortunately, in Earth’s orbit, where this radiation can be easily received, there is a gamma-ray telescope: Fermi Space Telescope He’s been observing the high-energy sky since 2008. Aditya Parthasarathy and Matthew Kerr wondered if the gravitational wave signal from millisecond pulsars could also be detected in the gamma-ray band. Answer: Yes you can. As a result, twelve years of data were made available to experts in one fell swoop. Published results Fermi-LAT recently collaborated in “Science” magazine.

“The good thing is that we don’t even have to do that much because Fermi is in orbit around the Earth and is scanning the whole sky from there,” says Aditya Parthasarathy. “It works so well that we can even detect low-frequency gravitational waves ourselves, without PTAs in the radio wave band. It’s a completely independent method.”

However, Aditya Parthasarathy still has to be patient. Although he and his team were able to show that the method works in principle, they simply didn’t collect enough data here either. This also applies to gravitational wave hunters in the gamma ray range: welcome to wait.

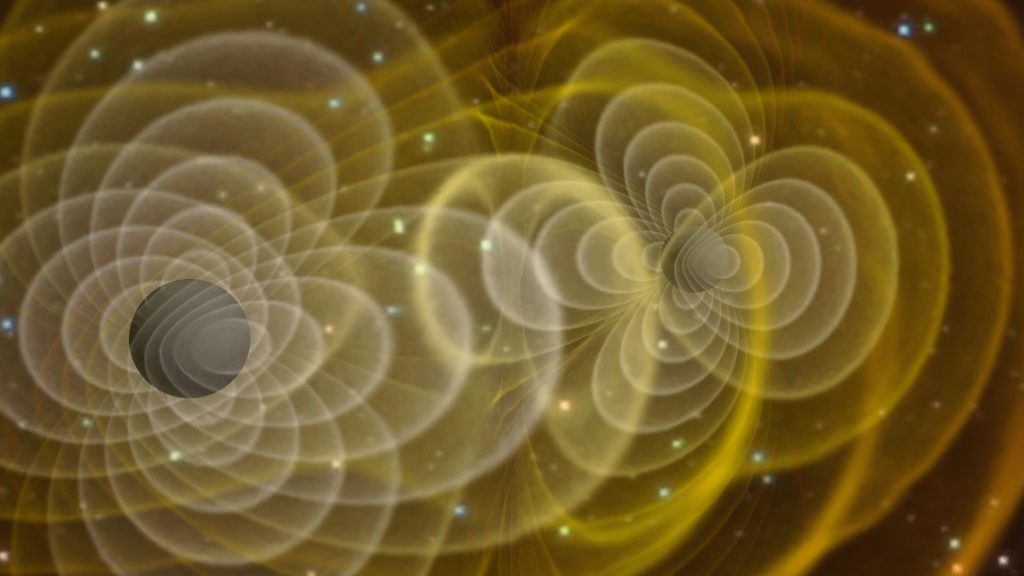

As researchers wait for the first data on the gravitational-wave background, they ask themselves what they can actually observe. What creates a gravitational wave signal? Because it’s not the hum of a single pair of compact black holes that describe the Hillings Downs curve. Instead, it’s a superimposed signal from the many extremely massive black holes that migrate to the new common center when two galaxies collide and orbit each other there. This is why researchers are also talking about a random gravitational wave background.

If black holes are too boring for you, what about cosmic strings?

However, other processes in space can generate such low-frequency gravitational waves. Theoretical physicist Kay Schmitz deals with them. He would like to be on the lookout for signs of cosmic strings, the remnants of the universe’s time right after the Big Bang. Such cosmic strings could indicate phase transitions our world was going through at the time — and would be a direct indication of physics beyond the Standard Model. Or perhaps the Hellings-Downs curve hints at cosmic inflation shortly after the Big Bang, which caused spacetime itself to oscillate?

More Stories

Coral Seeding: Artificial Insemination Makes Coral More Heat Tolerant

Fear, Anger, and Denial: How People Respond to Climate Change – Research

LKH Graz: Using radiation to combat heart arrhythmias