Two cancer-causing genes also regulate metabolism in the liver

The global obesity epidemic has increased the risk of fat accumulation in the liver, which is a precursor to hepatitis and liver disease. However, a puzzling paradox is the development of fatty liver in thin, normal-weight individuals and individuals following a healthy diet. Scientists know that two genes, RNF43 and ZNRF3, are mutated in liver cancer patients. However, their role in developing liver cancer was not previously known. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden report that a loss or mutation of these genes in non-obese mice fed a normal diet leads to fat accumulation and inflammation in the liver. These genetic changes not only lead to an increase in fat accumulation, but also to an increase in hepatocytes. In humans, these changes also increase the risk of NASH and fatty liver disease and shorten the life expectancy of patients. These findings could facilitate the identification of people at risk and enable new therapeutic measures and better treatment of the disease.

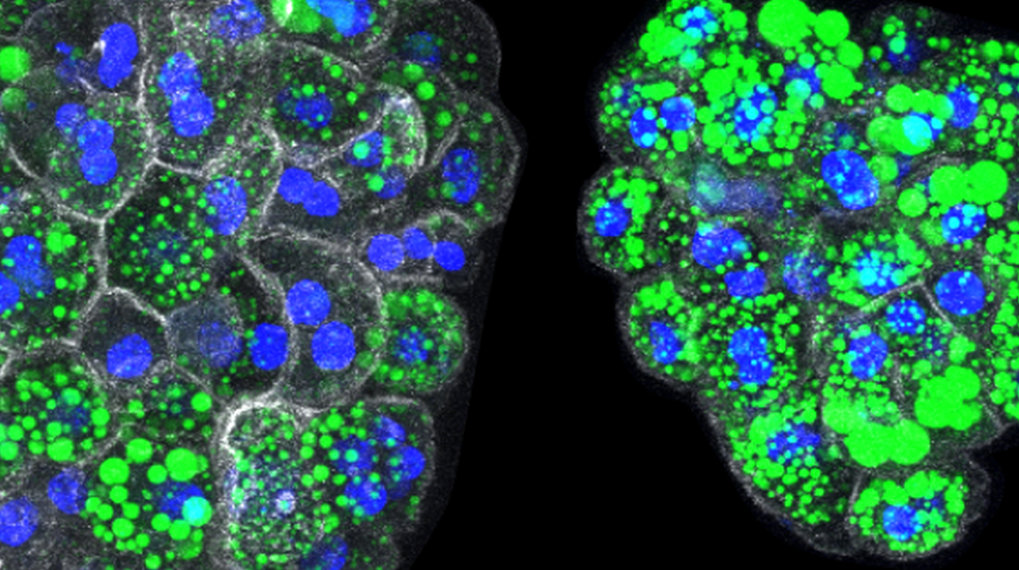

Organoids of normal (left) and mutant (right) mice hepatocytes with lipid accumulation in green. When the two genes (RNF43 and ZNRF3) are mutated, hepatocytes produce higher levels of lipids on their own, which also accumulate as large droplets within each cell (identifiable by the nuclei in blue and the surrounding cell membrane in white).

© Belenguer et al. Nature Communications 2022 / MPI-CBG

The liver is our central metabolic organ, essential for detoxification and digestion. Chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH, hepatitis) and liver cancer are on the rise worldwide, resulting in two million deaths each year. Therefore, it is more important than ever to understand the causes and molecular mechanisms underlying liver disease in order to prevent, control and treat the increasing number of patients. Previous cancer genetic studies identified RNF43 and ZNRF3 as mutated genes in colon and liver cancer patients. However, their involvement in liver disease has not been explored. The Meritxell Huch research group at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, along with colleagues at Gordon Institute (Cambridge, UK) and in Cambridge University Investigate the mechanisms by which changes in these two genes can influence the development of liver disease.

To get to the end of this question, the researchers worked with mice as an animal model, with data from patients, human tissue, and so-called liver organoid cultures, which are three-dimensional cellular micro-structures made of liver-like liver cells. In a bowl. Germán Belenguer, first author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in the Meritxell Huch group explains: “Using the organoid, we were able to grow only hepatocytes that were mutated in these genes, and we saw that the loss of these genes triggers a signal that regulates fat metabolism. As a result. Fat metabolism is no longer under control and fat accumulates in the liver, which in turn leads to fatty liver. In addition, active signaling causes uncontrollable proliferation of hepatocytes. Together, the two mechanisms promote the development of fatty liver disease and cancer.”

Less chance of survival

The scientists then compared results from the trials with patient data in a publicly available data set from the International Cancer Genome Consortium. They examined the chances of survival when the two genes mutated in liver cancer patients and found that patients with these mutated genes had fatty liver disease and had a worse prognosis than liver cancer patients who did not have the two mutated genes.

“Our results could help identify people with an RNF43/ZNRF3 mutation who have an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma or fatty liver,” Meritxell Huch explains. She adds: “With the alarming increase in consumption of fat and sugar worldwide, it may be important for therapeutic procedures and disease management to identify individuals who are susceptible to it due to their genetic mutation, especially in the very early stages or even before the onset of the disease. We will need more Studies to characterize the role of the two genes in human fatty liver disease, NASH, and human hepatocellular carcinoma, and to identify therapies that can help those patients who already have a natural predisposition to developing the disease.”

“Total coffee aficionado. Travel buff. Music ninja. Bacon nerd. Beeraholic.”

More Stories

Coral Seeding: Artificial Insemination Makes Coral More Heat Tolerant

Fear, Anger, and Denial: How People Respond to Climate Change – Research

LKH Graz: Using radiation to combat heart arrhythmias